MMPI believes that modern-day decision makers are guilty of mistaking urgency for importance. Urgency is unhelpfully defined as “the state of being urgent”. It derives from urge – an impulse that impels us to decide. Synonyms include criticalness, cruciality and necessity. This suggests a swift action is required, which must be important. But is it?

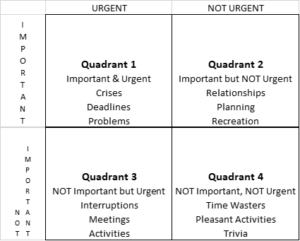

Researchers have long suspected that the notion of urgency presents the brain with a cognitive bias. A sense of urgency extricates us from our torpor and stops us forever procrastinating. But, somehow, we see the urgency as a priority – a task that must be completed. Its imperative nature attracts significance and makes the action seem essential. However, just because a task is urgent doesn’t necessarily mean that it is important. US President Eisenhower proclaimed, “What is important is seldom urgent and what is urgent is seldom important.” He is also accredited with the following summation.

Even allowing that this was written in a bygone era, we can still see crossovers with modern society. For instance, “time wasters” could easily be those repetitive pesky e-mails with annoying cut-offs….3 days left, 2 days left, etc. – often promoting something that we don’t want; but the deadline draws us in. We have a bias towards completing urgent tasks regardless of their importance. And, as a consequence, we delay non-urgent activities, which may be much more important. This makes us less productive since we devote more time to less significant matters and spend valuable time remediating important issues that we should have prioritised.

We are all familiar with these issues. We start the day with a great plan but then get swamped by a barrage of e-mails, phone calls, meetings, etc. We subconsciously choose to select urgent tasks as a priority even though intuitively this makes no sense. Our brains are predisposed to deferring important work in favour of jobs that mistakenly seem more vital.

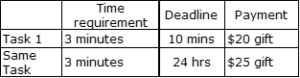

Researchers carried out a simple experiment by asking volunteers to perform the same task but with different deadlines and different rewards.

Incredibly, in every instance, people chose to eschew the $25 pay-out in favour of the one with the tighter deadline – because the perceived urgency was deemed more important. The logical goal of securing an extra $5 for the same work gets clouded out by our urgency bias. It’s totally irrational and yet we do it all the time in our everyday business.

We should practise more at recognising that urgency may not be all that important and that non-urgent matters, lurking in the background, deserve more attention. Computerised diaries and other prompt systems are programmed to follow a prioritisation pattern that promotes time pressures. This forces us to adopt a discipline of deadlines and task-completion steps. Because we are immersed in imposed rules, we find it difficult to break out of the cycle.

Try forcing yourself to identify tasks that are important; to defer those that are less important; and to ignore those that are trivial. It’s not easy but it’s highly rewarding!